Projects are therefore a must for organizations that want to remain viable. This means that all companies are dependent on projects, from small to medium-sized companies to big corporations. The number of measures and staff involved is correspondingly large, and things can become chaotic.

This white paper shows how multi-project management gets to grips with this chaos and helps achieve the desired successes in several parallel projects through structure and clarity.

2 Why projects fail – and why they don’t

If almost every company does projects now, how can it be that these projects fail time and time again? Should we not assume that projects will automatically be organized by project management at some point?

The simple answer: no; for various reasons.

a) There are those companies that do "a bit of project management", but they are not professional enough, and they do not think it is very important to give themselves and their projects structure.

b) Or companies that recognize that project management is useful, but do not attach enough importance to it. In this case, the role of the project manager is not sufficiently valued. It is often perceived by project staff or even managers as a "hobby"; a dual role in addition to implementing the project.

c) Ad-hoc projects take up all the management's attention, but only if a real danger to sales, reputation, etc. threatens. Then additional budgets, resources and other facilities are suddenly made available, but at the expense of all other projects, which have to contend with cost savings. 1

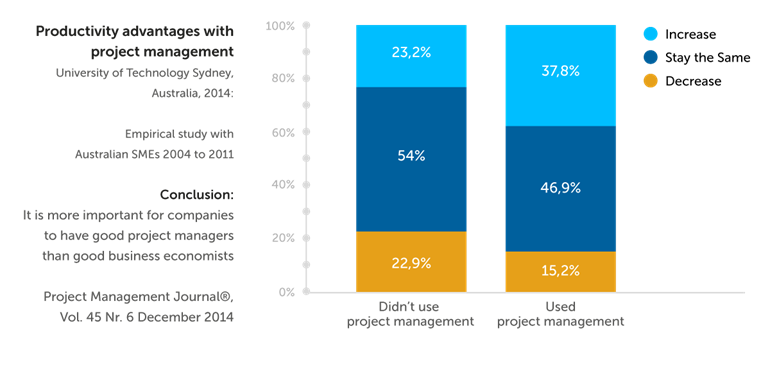

Many studies, however, show that professional project management has real productivity advantages and therefore deserves more attention. An empirical study from Australia, conducted between 2004 and 2011 in small and medium-sized companies, is an example.

It shows that compared to companies without project management, companies with project management were far ahead in terms of productivity, and were simply more successful!

The other side of the coin, however, is that projects are started more and more quickly without a proper requirements assessment or compa- rable evaluation being done. But the chances for the success of the project only increase when exactly what is needed for a project is known. This is where the attention of the management is required - not just when “fire-fighting” due to a lack of structure and scarce resources.

Projects also “catch fire” when too much happens at the same time and the big picture is lost sight of. That would not be a problem if the organization was done in advance. The following questions can help:

Are we doing the right projects at the right time?

The small, but subtle difference; the question is not about quantity but accuracy.

Do we have sufficient capacity?

In both monetary and human resources?

Who will take charge of the projects in the long-term?

After all, not every project is designed for a short time, but can last several years. So who will hold the reins for five years?

Adding all these parts together creates a holistic picture of what successful projects require: a clear structure. This is especially true when several projects run in parallel. What could be more appropriate here than multi-project management?

3 First of all: the components of a project

Before setting up a structure, we must clarify the components in a project and which roles these components play. Various units of meas- urement are suitable. Is it a question of micro-measures or a matter of major strategic issues that are important in the context of a longer-term objective? Size parameters for estimation should also be defined. These can be found in resources, budgets, number of activities, etc. The higher the complexity, the more guidelines and rules have to be considered, and the more essential it is to define the priority in the higher-level context.

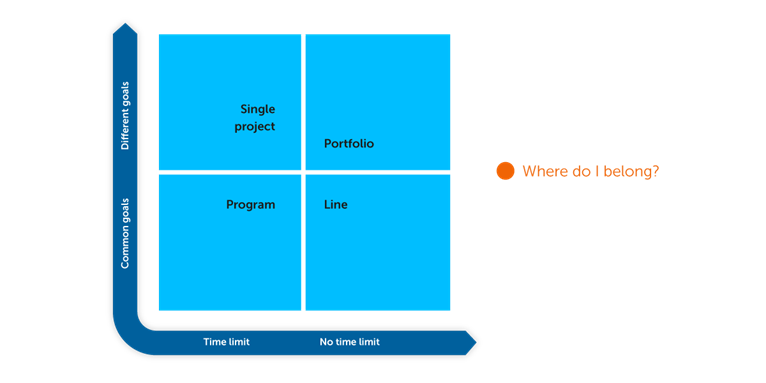

a) Project

We speak of a project as soon as we have a very specific goal that cannot be implemented within a single department. So, we need additional structures to the usual organization chart. A project objective, in turn, is once again outlined using time, cost and quality requirements.

b) Program

Programs pursue an operational long-term goal. All individual fixed-term projects and measures, which are to be applied to this overall objective, are summarized under a program. With programs, small companies also have the chance to manage complex projects more effectively by structuring them, and to keep an eye on requirements and individual projects and measures.

c) Portfolio

By contrast, a portfolio relates to an indefinite term. In this context, projects which pursue different objectives are also combined, but this is done with common strategic considerations. The goal of the portfolio is to identify the key issues and the number of projects currently assigned to specific issues in the company. Let’s take "Innovation" as an example. All projects, which contribute to innovation in some way, are given this label. So, it is possible to see when the workload in this area becomes too much. And a project can be assigned to various portfolios.

In short, a portfolio is a summary of projects and programs that help to develop and implement a company strategy in the long term.

This results in different perspectives on individual projects:

A project has a project manager. If this project is part of a more complex project landscape with a single goal, the program manager joins the project. In addition, one or more portfolio managers may be able to "observe" our project for strategic or innovative reasons.

Let's take a look at the examples here and choose Daimler-Benz and the portfolio "C-Class". This will include not only projects such as "engine", "fuel cell" or "interior" but also "Formula 1" and "DTM" - and thus various people and their responsibilities.

This means, however, that the healthy selfishness of a project manager within individual projects can only continue to apply to individual projects. As soon as a common, overall objective is being pursued, thanks to mul- ti-project management, everyone should hopefully be “pulling in the same direction".

4 Three steps to a successful project

Important steps have been taken to achieve order and structure in multi-project management. However, there are other aspects which are indispensable to successfully manage the flood of projects.

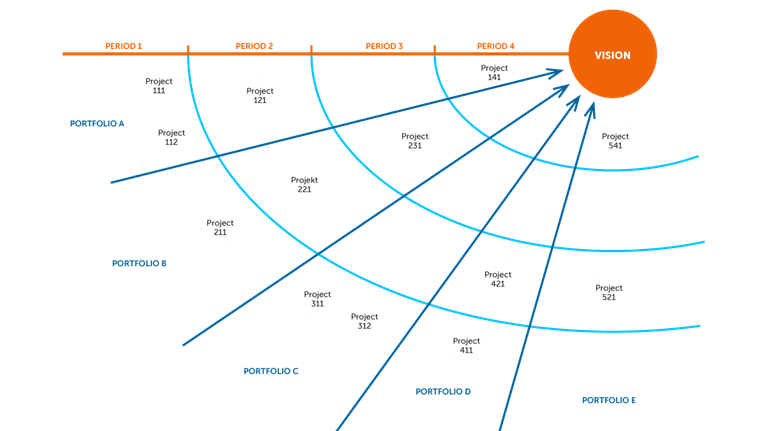

a) This includes the project strategy using Portfolio management.

It is the link between corporate strategy and operational management, as most strategic objectives are now implemented through projects. This is why portfolio management is responsible for managing and prioritizing these projects.

- Which projects must be implemented with which objectives?

- Which projects are there in the company at all?

- Where is the "portfolio pot" overflowing and when can we bother which business area with which project?

- What is the importance of individual projects within the portfolio?

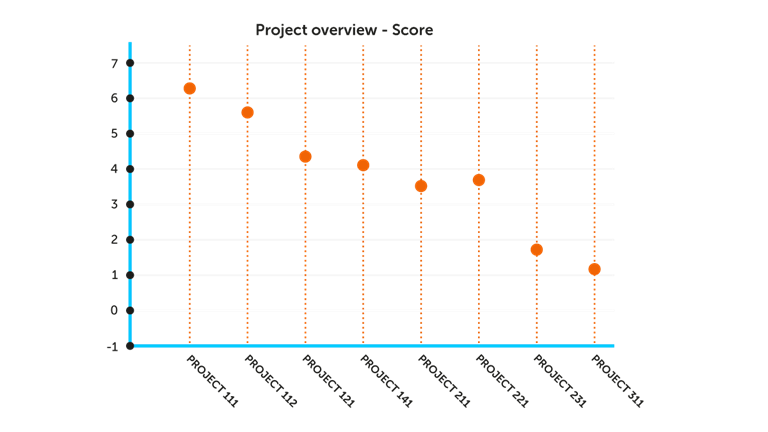

b) This results in the next step; Scoring.

Scoring supports the prioritization of projects, which are subjected to a so-called assessment, which is nothing more than answering questions, such as, "How important is the project for the future of our company?" Or "What happens if we do the project later or not at all?" Depending on the answers, points are awarded, which result in a total score.

This allows the weighting of the individual project, and helps the portfolio manager. With these comparative figures, which can be transferred to a multi-project management system and visualized, he/she can now confront the management and demand decisions regarding projects. This is not the end of the discussion, but helps conduct substantive and well-founded discussions.

c) Program management is also crucial.

A reminder; a program is a group of projects that serve a common goal. This program is coordinated by the program manager. For example, when building a house, the program manager makes sure that all project managers (in charge of painting, new floor coverings, new facade, etc.) pursue their goals and fulfill them within the framework set without harming each other.

4 SUMMARY

By arranging projects according to complexity, short-term (program) and medium/long-term goals (portfolio), multi-project management makes it possible to clearly identify what certain projects focus on thematically. An additional objective weighting using project scoring also helps with resource conflicts in prioritizing the order of projects.

All three factors combined offer the management of a company, regardless of size, the possibility of more transparent and, above all, more comprehensible decision-making. This, in turn, makes it possible to make better decisions, which also benefit multi-project manage- ment.

Multi-project management lives from structure and decisions while simultaneously providing them.

Read it again

Download the PDF version to share or read again in your own time.